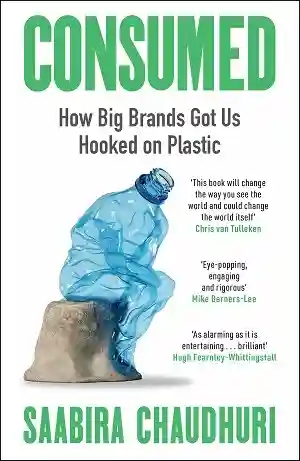

We are thrilled to welcome Saabira Chaudhuri to Storizen for an exclusive conversation around her powerful new book, Consumed: How Big Brands Got Us Hooked on Plastic. A seasoned journalist and former consumer goods correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Saabira unravels the gripping story of how everyday items like single-use sachets reshaped global consumer behavior and deepened the plastic pollution crisis. With sharp investigative insight and a narrative style that reads like a corporate thriller, Consumed shines a critical yet balanced light on the forces driving our plastic dependency—and the choices we still have to reclaim control. In this interview, she shares the untold stories behind the packaging revolution, the surprising truths about “Big Plastic,” and why storytelling itself can be a tool for environmental change.

In “Consumed”, you highlight the story of the single-use sachet as a turning point in global consumer culture. What surprised you most when uncovering its journey from innovation to environmental crisis?

What surprised me most was how integral the package itself was to the creation of demand – it didn’t just protect the product, it was the most important part of the product. The single-use sachet, made from layers of plastic, literally built a market for packaged shampoo in India where one previously didn’t exist.

One of the Hindustan Lever execs I interviewed, Harsh Bahadur, told me how many Indians in the 1980s didn’t know what packaged shampoo was – they didn’t use it. This doesn’t mean people didn’t wash their hair – they did but they used homemade concoctions from reetha and amla or bar soap, and oil to condition hair.

To convince Indians to abandon this traditional way of caring for their hair, companies like Unilever and Procter & Gamble – who saw in India an enormous untapped market for packaged shampoo – took a two-pronged approach.

First, they poured big money into advertisements to convince Indians of the desirability of the Western ideal of flowing, shiny, straight hair. Brands like Sunsilk and Pantene were the only ones who could deliver this, was the message delivered to millions of Indian women who had long worn their hair in braids or buns, which made a lot of sense in the heat.

Second, they found a way to deliver the product to Indians across the country very cheaply. Light, portable, robust and sized to contain enough shampoo for a single wash, the nonrecyclable, multilayer plastic sachet gave companies a vehicle to turn a fat profit in a poor country.

The other thing that surprised me was just how ubiquitous the sachet became – its success in India and other parts of Asia paved the way for tiny plastic packages to be used in emerging markets all over the world not just for shampoo but a whole range of everyday items.

You maintain a tone that’s critical yet non-moralizing throughout the book. How did you strike that balance when interviewing powerful corporate figures and environmental activists with competing narratives?

I covered consumer goods companies at the Wall Street Journal for over a decade and during this time every story I did was based on reporting rather than opinion. One of the Journal’s maxims is “show the reader, don’t tell the reader” or in other words, let your reporting speak for itself.

Of course a book is different to a Wall Street Journal story, I do have my own world view, and I did need to insert some of my opinions into this book for it to be impactful but by and large I adopted the same principles I used while reporting for my day job.

This meant being curious and open minded about what the CEOs and marketing heads were telling me as well as being open to what the environmental activists were saying. It meant acknowledging the many benefits plastics bring as well as telling readers about their many downsides. It was very clear that the various camps I interviewed for Consumed all had their own agendas – I tried not to get too mired in taking sides but instead focused on bringing these different perspectives together in a narrative that largely allows my readers to draw their own conclusions.

One of the big weaknesses of environmental books is how divisive they can be – authors often make very declaratory statements, they make no attempt to see where their opponents are coming from, and much of what’s said is based on the opinions of a very select group of people. Narratives can be very overly simplistic – there are “good” environmentalists and “evil” companies – and this alienates many readers. I wanted to strive for a narrative that was more credible, nuanced and realistic even if the tradeoff is that it made the story less seductive.

I’d like people to walk away knowing that it doesn’t have to be this way – that things can be different. Often big topics like climate, plastics and recycling can feel out of our control, leaving people feeling a bit despairing or depressed.

Saabira Chaudhuri

The book reveals the deliberate tactics used by ‘Big Plastic’ to delay regulation. Were there moments in your investigation when the extent of this manipulation truly shocked you?

The thing I found very surprising was the extent of the similarity I found between the playbook used by companies today to forestall bans or restrictions and burnish the plastics industry’s reputation and that used in previous decades, going back to at least the 1970s. Three examples:

- The plastics industry regularly tells regulators and consumers about the essential role of its durable products in healthcare and transport as a way to divert attention from concerns about single-use plastic bags, cutlery, fast food containers, straws and unnecessary food packaging most of which gets used for a few minutes before being landfilled, dumped or burned. Most people aren’t concerned about the plastic used in bike safety helmets or airplanes but the plastics industry runs campaigns touting the benefits of plastics in these areas that in no way address the concerns people have about disposable plastic that being used unnecessarily.

- The plastics industry continues to push recycling as its number one solution even though it’s been clear since the 1980s that recycling can only effectively deal with a very small subset of plastics – it simply isn’t economical to recycle hundreds of subtypes that use various chemicals and various pigments. Earlier this year the U.S. Plastics Industry Association set up the “Polystyrene Recycling Alliance” which is a mirror image of the “Polystyrene Packaging Council” created in the1980s to fight bans and push the message that polystyrene is easy to recycle (it isn’t for a variety of reasons I lay out in Consumed.)

- The industry’s argument has long been that any bans, taxes or other restrictions on single-use plastics will massively raise costs for consumers and do little to cut waste. It has been making this same argument since the 1970s when container deposit laws (which charge a refundable deposit on drinks containers) were being rolled out across the U.S. Meanwhile, costs for consumers keep rising anyway and estimates about the otherwise uncounted costs for our environment and our health from things like biodiversity loss and the impacts of chemicals and microplastics continue to climb.

One of the big weaknesses of environmental books is how divisive they can be – authors often make very declaratory statements, they make no attempt to see where their opponents are coming from, and much of what’s said is based on the opinions of a very select group of people.

Saabira Chaudhuri

You’ve managed to turn a topic as heavy as plastic pollution into something that reads like a thriller. Was that a conscious storytelling strategy to reach readers beyond the usual environmental circles?

I struggle to get through a lot of non-fiction – it can feel dry, slow and repetitive – so I ultimately set out to write the sort of book that I enjoy reading. My hope is that Consumed resonates with people interested in marketing, consumer psychology, history and business strategy just as much as it does with those who worry about the environment.

My reporting style has evolved over the years to be more people-focused and I’ve found having a narrative vehicle through which to explore a larger issue is really helpful in terms of keeping readers engaged and bringing an otherwise dry, unrelatable issue to life. This doesn’t suit everyone – I’ve had a couple of critical reviews from people who think my describing the physical appearance and background of P&G’s main PR person for diapers for instance is pointless. But largely the feedback has been that people find having an image of the main characters – and their personality traits – to be helpful in then being able to understand not just the individual motivations of these characters but also the motivations of their employers who are very big companies that otherwise feel faceless and impersonal.

If readers were to walk away with one change in mindset or behavior after finishing Consumed, what would you hope that to be?

I’d like people to walk away knowing that it doesn’t have to be this way – that things can be different. Often big topics like climate, plastics and recycling can feel out of our control, leaving people feeling a bit despairing or depressed.

I hope to counter this by showing that life worked just fine before we were all seduced by disposable packaging and that there are ways to pressure big companies to change how they do business. Consumed shows time and again how badly consumer goods companies want us – their consumers – to like them, and how they need our approval for their brands to keep selling. We can use that power to hold companies accountable, to push them to do better.

Ultimately, being aware of how companies have manipulated us into developing “needs” we never once had can be empowering since it gives people the motivation to take back control and make decisions that take into account not just convenience and cost but also the wider impact our everyday choices are having on our health and our planet.