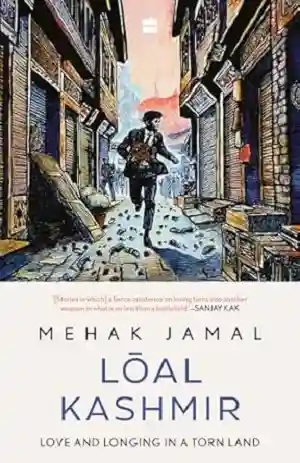

Kashmir has long been a region of paradoxes—beauty and turmoil, love and loss, resilience and silence. In Lōal Kashmir, the author, Mehak Jamal takes readers on an intimate journey through the deeply personal and often untold stories of love, connection, and survival in the valley. From the abrogation of Article 370 to the everyday realities of curfews and internet blackouts, the book sheds light on how Kashmiris navigate relationships amidst conflict. In this conversation, the author reflects on the challenges of gathering these stories, the weight of being a storyteller in a place where silence is often enforced, and how love—whether romantic, familial, or ideological—emerges as an act of quiet defiance.

What inspired you to write “Lōal Kashmir”, and how did spending time with your interviewees deepen your connection to your Kashmiri roots, especially given your mixed heritage?

I was inspired to write Lōal Kashmir after the abrogation of Articles 370 and 35A in 2019. The long and jarring communication blockade after the event brought a lot of stories of human connection to the fore. What intriguedme most were the stories of love—how people were finding innovative ways to reach out and communicate with each other through the imposed silence. I spoke to over seventy people during the course of my interviews. In many ways I felt like their secret keeper as quite a lot of them wanted to remain anonymous. That they trusted me with their life stories certainly made me feel closer to them and to Kashmir.

Gathering and curating deeply personal narratives is no easy task. What was your experience like during this process, and what were the biggest challenges you faced in bringing these stories to life? Additionally, did these stories influence or change you in any way?

I was very overwhelmed with the number of people who wanted to tell me their stories when I put out the project call. It was unexpected to say the least. But as I started engaging with all the contributors and heard them pour their hearts out to me, I knew that for a lot of them, this wasn’t something that was inquired about enough. Thus the excitement to bring to light these narratives was imperative for me. It took me four years—from starting the project to the book releasing—and towards the end of the journey, one huge challenge I faced was that I needed to get permissions from the contributors as per my publisher’s mandate for non-fiction books. When I was interviewing the contributors, this hadn’t crossed my mind. It had been two-three years since I had conducted the conversations with them, and when I went back for the permissions, as I feared, I lost a few stories in the book; the contributors had changed their minds. They had different reasons for this, but one of the biggest one was the unsaid pressure that many Kashmiris feel not to speak up and keep their head down. But I couldn’t coerce people into doing something they weren’t comfortable with. The stories have been with me for a long time, so it did hurt me a little to let go of those particular accounts. I realized that all of the stories in the book haveinfluenced me in one way or other, especially to look beyond the surface when it comes to Kashmir.

With the book unfolding across three distinct periods, what insights does it reveal about how conflict has shaped the experience and expression of love in Kashmir? Were there any nostalgic moments that stood out to you while writing these chapters?

The very fact that the stories span across three time periods and yet the stories of love have similar elements in them, shows how enduring the Kashmir conflict is. So much has changed over the years, but how people live and love through the unrest remains similar, if not the same. In Kashmir, love is an act of resistance, a form of expression for the Kashmiri people to tell the world that they are very much still here. Having grown up in Srinagar, of course I have gone through some of the time-periods in the book myself. There are moments in the book that are reminiscent of my childhood and teenage years, and I have been able to draw from my own memories to make the reading of the book more authentic.

Communication becomes a struggle in times of curfews and internet blackouts. How have these restrictions reshaped emotional connections and resilience among Kashmiris?

Communication is a basic right; phones and internet are more so in today’s day and age. The fact that they can be taken away from a people just like that and not resumed for months is unthought of for the general populace. Yet, this happens in Kashmir all the time. There is no romaticising this curtailment on basic necessities and nor does the book do that. The book merely shows how it is to live in Kashmir through these blockades, curfews and unrest—there’s no hiding from them—and still, how these lovers seek to break through the silence and get their voices across. It is not only an act of love, but also an act of resilience.

Your book explores love beyond the romantic through familial, platonic, and ideological bonds, offering a broader perspective on human connections. What key message does this convey to readers, especially in the context of Kashmiri society, where love remains a complex and often taboo subject?

Kashmir holds within it many complexities and contradictions that do not often get heard as the conflict takes the foreground in many conversations, as it should. Lōal Kashmir just takes a moment to throw light on the lives of Kashmiris in conjuction to the unrest, rather than taking attention away from it.Afterall, their lives are informed by it. The result is the inner lives of people that they would normally not want to talk about, either because they deem these memories unimportant or they think them a taboo. Love is not a complex subject. Neither should it be, ever. Lōal Kashmir pays homage to it by making these stories of love an eminent part of conversation when it comes to talking about the valley.

How has your background in filmmaking influenced your writing style, both as a strength and a challenge? Did approaching stories with a cinematic structure help you make sense of the nonlinear way people share their experiences?

The main challenge came in the form of discovering my prose language, that was often influenced by my screenwriting language—and they do not go hand in hand. It took some trial and error, but I was able to uncover a distinct voice for the book. Screenwriting however had its advantages as well. While interviewing people, they often narrate in a nonlinear way, so my screenwriting mind was able to make sense of their narratives and present them as free flowing stories, rather than meandering accounts.

Check out our Latest Book Reviews

As a writer, filmmaker, and someone from Srinagar, how would you like the rest of the country to perceive Kashmir in a more captivating and positive light?

Kashmir does not need to be seen in a captivating and positive light, rather it needs to be perceived with an urgent sense of inquiry, and empathy for the place and people—to understand what Kashmiris have been trying to say for years. Kashmir is much bigger than its snowcapped mountains, autumnal Chinars and varied handicrafts. It contains within it multitudes and the onus to present itself in a positive light should not be on Kashmiris. If you are curious about Kashmir, its people and what the enduring unrest in the valley is about—start by reading their stories.

Books are love!

Get a copy now!